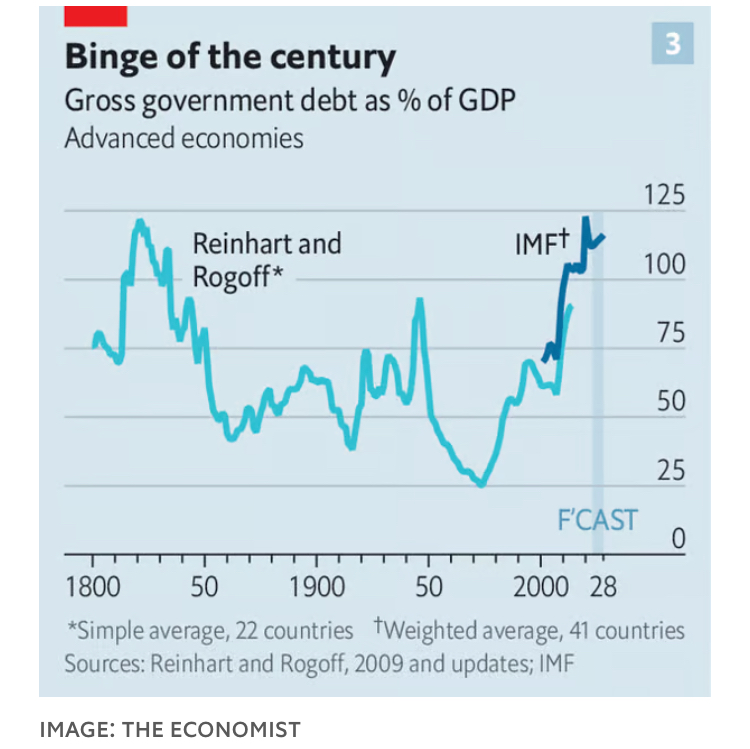

The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level. By John Cochrane. Princeton University Press; 584 pages; $99.95 and £84

An economics professor at Stanford University builds a new(ish) theory for how government debt, not interest rates, ultimately determines prices. Not for the faint-hearted, this book is provocative to economists and well timed for an age of big deficits and high inflation.

Best Things First. By Bjorn Lomborg. Copenhagen Consensus Centre; 314 pages; £16.99

A forceful argument to replace the un’s sprawling and vague Sustainable Development Goals with 12 cost-effective policies to help the world’s poor. “Some things are difficult to fix, cost a lot and help little,” the author writes. Others can be solved “at low cost, with remarkable outcomes”.

Material World. By Ed Conway. Knopf; 512 pages; $35. WH Allen; £22

The economics and data editor of Britain’s Sky News travels the world in this study of how six crucial materials—copper, iron, lithium, oil, salt and sand—have altered human history and underpin the modern economy. As countries seek to decarbonise, there is a battle raging to control their supply.

Scaling People. By Claire Hughes Johnson. Stripe Press; 480 pages; $30 and £21.99

Good books about the nuts and bolts of management are vanishingly rare. A former executive at Google and Stripe offers a practical guide to everything from giving feedback and delegating to running a meeting and building teams.

Milton Friedman. By Jennifer Burns. Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 592 pages; $35

The most complete biography of the economist who became a cultural symbol of the free-market era that captured the world in the 1980s. It documents Friedman’s essential role in economic policy and libertarian thought and shows his enduring relevance, despite the world’s protectionist turn.

The Blazing World. By Jonathan Healey. Knopf; 512 pages; $38. Bloomsbury; £30

A page-turning history of the 17th century in revolutionary England. This account of a time of religious and political turmoil, intellectual ferment, scientific innovation and media upheaval is accessible and abounds with contemporary resonances.

Judgment at Tokyo. By Gary Bass. Knopf; 892 pages; $46. To be published in Britain by Pan Macmillan in January; £30

A meticulously researched and authoritative account of efforts to prosecute and punish Japanese generals and politicians deemed responsible for some of the horrors of the second world war. The author, a former writer for The Economist, looks at why attempts to produce a shared sense of justice failed.

Revolutionary Spring. By Christopher Clark. Allen Lane; 896 pages; £35. To be published in America by Crown in June; $40

A historian at Cambridge traces the events of 1848—the year revolutions spread to almost every country in Europe. “Hierarchies beat networks. Power prevailed over ideas and arguments,” he writes. This scintillating book features a compelling cast of idealists, thinkers, propagandists, cynics, and argues that their sacrifices were not wholly in vain.

Magisteria. By Nicholas Spencer. Oneworld Publications; 480 pages; $32 and £25

The common misconception that science and religion are at odds is revised in a deeply researched history of the interplay between the two ways of understanding the world. Religion produced the critical thinking that welcomed scientific knowledge, and science was often inspired by appreciating forces beyond our ken.

Science and technology

The Coming Wave. By Mustafa Suleyman, with Michael Bhaskar. Crown; 352 pages; $32.50. Bodley Head; $32.50

A co-founder of DeepMind, a leading ai company (and board member of The Economist’s parent company) offers a cogent look at the technology’s potential to transform the economy and society, along with the risks of misuse and surveillance.